Learn about the circumplex model that we apply at Leanmote and why we use it.

Why does mood matter?

Moods are a “conscious state of mind or predominant emotion”. While emotions may last as little as a few seconds, moods represent the form of emotional experience that can last for several hours, for good or ill. Closely related to an individual’s wellbeing, moods can impact the ways people think and feel, how they interpret their environment, and ultimately how they act. As a form of emotional wellbeing, moods have the potential to take a toll on a person’s psychological and even physical health if they are not dealt with adequately.

Studies have also shown that mood states are relevant to the workplace. For example, when people feel exhausted, they often make riskier decisions (due to a tendency to minimise information processing, ‘cutting corners’ to preserve their cognitive resources). On the flip side, when people feel energised, they are more likely to help other people. When people feel angry or frustrated, they are more likely to engage in conflict or even aggression. When people are anxious they tend to be very risk-averse. Yet employees who feel enthusiastic tend to show greater initiative-taking and more proactivity (e.g. suggesting process improvements or trying to prevent problems). Moods, therefore, have the potential to influence a wide range of performance-relevant behaviours.

Moods are also contagious. Someone who is enthusiastic can infuse others in their team with their eagerness and engagement in a project. Yet someone who is cynical or anxious could have the same effect. This means that a single person’s mood has the potential to influence not only their own productivity but also the productivity of people around them.

So it seems that moods can have a big impact on a workplace, which is why Leanmote provides tools that quickly assess moods and track them over time.

Circumplex Model of Mood

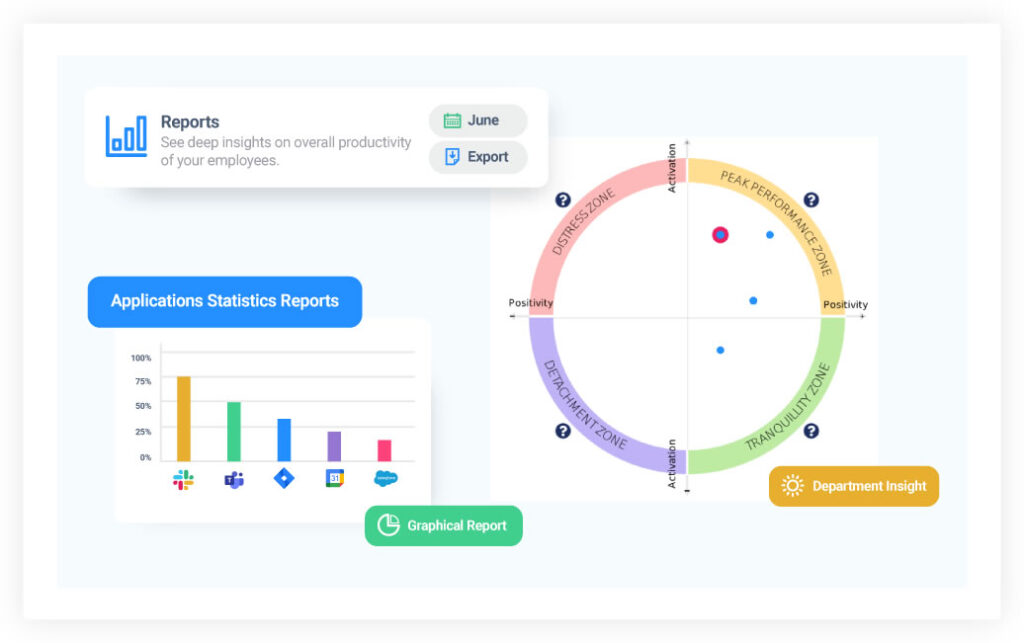

Given the variety of moods and the complexity of their effects, measurement of mood has the potential to be complicated, but it need not be. Circumplex models of mood provide a framework to understand most aspects of emotional experience in terms of two fundamental mood dimensions: Tempo and Positivity.

Many people think about moods in terms of a simple dimension going from bad to good. Some moods feel very good (e.g., delight, joy), while others feel very bad (e.g., anger, disappointment). This aspect of emotional experience is represented by a position along our horizontal dimension, Positivity. Better moods lie towards the positive end, while worse moods lie towards the negative end.

Many moods lie between the extremes of bad and good. And even looking at one end of the Positivity scale, two positive moods can be quite different in how they influence thoughts and behaviours. For example, most would agree that enthusiasm is a very different emotional experience to contentment. From this, it should be clear that a single dimension is not enough for understanding moods.

Our vertical dimension, Tempo, can be understood as the extent to which a person feels energized, ‘switched-on`, and ‘amped up’. Moods high in these activated emotional states are associated with higher levels of adrenaline. Someone scoring high in Tempo may be productively energetic, excited, or enthusiastic. Yet we should remember that moods such as anxiety and anger are also high in Tempo. Similarly, someone low in Tempo may feel detached, depressed, or drained, and yet contentment and tranquillity are also low in Tempo.

In short, to understand and be able to make useful predictions from mood (in terms of health and productivity), it is important to combine these two dimensions. We use a model that represents, in two-dimensional space, a wide variety of different emotional experiences. For example, the mood of excitement includes the features of high positivity as well as high tempo, whereas depression can be characterised as being low in both positivity and tempo.

The ability for people to track their moods across the two dimensions allows insight into patterns of emotional wellbeing. With this understanding, more power is given to the individual to monitor and influence their own mood.

Mood Zones

By measuring mood within a circumplex model, Leanmote can categorise the great variety of discrete emotional experiences into four quadrants or zones, each capturing a set of similar moods that have been seen to have a similar set of causes and consequences.

High Tempo, Low Positivity: The Distress Zone

- This zone is characterised by moods in which tempo is high but positivity is low, such as fear, anxiety, anger, and frustration.

- These moods can be triggered by high work pressures, by a lack of time or other resources, by suboptimal team experiences, or by other problems.

- Employees in this zone tend to be highly alert (especially to risks) and can be highly productive for short periods, but they are more likely to make mistakes, they usually feel stressed, and the longer they spend in this zone the higher is their risk of burnout.

High Tempo, High Positivity: The Peak Performance Zone

- This zone is characterised by moods in which tempo and positivity are both high, such as excitement, enthusiasm, eagerness, and enjoyment.

- These moods can be triggered by the presence of good teamwork and other effective work resources, and/or by opportunities to learn and engage in tasks that are interesting and which make employees feel valuable.

- Employees in this zone tend to be highly engaged with their work and absorbed in their tasks, and so they can display high levels of productivity and innovation. Nevertheless, prolonged periods in this zone can also be draining unless good self-care practices are utilised.

Low Tempo, Low Positivity: The Detachment Zone

- This zone is characterised by moods in which tempo and positivity are both low, such as exhaustion, depression, disappointment, and discouragement.

- These moods can be triggered by a lack of effective work resources, by a lack of recognition for effortful contributions, by problematic team climates, or simply as a result of having been placed under too much pressure for too long.

- Employees in this zone tend to withdraw from their co-workers, their clients, or even their responsibilities; they may be dealing with early stages of burnout and if they remain in this zone for long their burnout may worsen.

Tranquillity Zone

- This zone is characterised by moods in which tempo is low, but positivity is high, such as satisfaction, contentment, and calmness.

- These moods can be triggered by the presence of effective work resources combined with sustainable workloads, along with a lack of apparent risks or problems in the near future.

Employees in this zone tend to be more tolerant of obstacles, more likely to cooperate, and more willing to try new things.

How does mood-tracking help me?

People who regularly identify and track their moods become more aware of those moods. High mood awareness is an important aspect of emotional intelligence. For example, and studies have shown several benefits associated with mood awareness:

- People who are more aware of their moods are better at recognising factors that impact their moods (causes and triggers), and also better at understanding the consequences of moods on their behaviours.

- People who are more aware of their own moods have greater opportunity and capacity to manage their moods, rather than letting their moods determine their experiences. For example, people with more mood awareness are less likely to take their frustrations out on others.

- People who are more aware of their moods can learn to utilise their moods to their benefit. For example, they may be able to maximise their efficiency by focusing on tasks that are enhanced by their current mood.

Ultimately, tracking your mood provides an opportunity for improved awareness of one’s emotional experiences, and further reflection can bring about meaningful insights into how to manage one’s situation to suit one’s mood, or how to manage one’s mood to suit one’s situation. Leanmote provides tools to support this insight into personal wellbeing and capability.

Mood and management

As managers develop an understanding of their overall team’s wellbeing and mood, they too are able to reach a level of emotional intelligence and awareness that aids their wellbeing and productivity. They can become more aware of how their own moods might be influencing their teams, which may not always have been ideal, and they can reflect on ways they can manage their moods more effectively.

But Leanmote’s tools also allow managers insights into the moods of their team members. In an increasingly virtual world of work, insights into team members moods and wellbeing can be difficult to obtain. Having the opportunity to observe team members moods helps managers to recognise when employees require assistance. Our tools can help managers work with employees to formulate solutions that support wellness and facilitate productivity. The process contributes not only to team support but also to ongoing leadership development.

Bibliography

Avramova, Y. , Stapel, D. , Lerouge, D. & (2010). Mood and Context-Dependence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99 (2), 203-214. doi: 10.1037/a0020216.

Hockey, G. R. J., John Maule, A., Clough, P. J., & Bdzola, L. “Effects of Negative Mood States on Risk in Everyday Decision Making.” Cognition and Emotion, vol. 14, (2000) pp. 823–55,

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Mood. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved September 12, 2021, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/mood

Peter Warr , Uta K. Bindl , Sharon K. Parker & Ilke Inceoglu (2014) Four-quadrant investigation of job-related affects and behaviours, European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 23:3, 342-363, DOI: 10.1080/1359432X.2012.744449

Rivera-Pelayo, V., Fessl, A., Müller, L., & Pammer, V., Introducing Mood Self-Tracking at Work: Empirical Insights from Call Centers., 24(1), 1–28. edn ([n.p.]: ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 2017).

Stewart-Brown, S. (1998). Emotional wellbeing and its relation to health. BMJ, 317(7173), 1608–1609. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.317.7173.1608